Margaret Lawrence was born on April 10, 1709 in Wem, Shropshire Co., England, the presumed fourth child of Thomas Lawrence* and Mary Peploe*. Margaret was also christened on April 10, 1709 at the Battlefield Parish Church at Battlefield, Shropshire County, England. As a young woman, about 19-20 years old, she was banished from Wem, England, because she left the Church of England for the Puritan Faith. Margaret was residing in London, Middlesex Co., England, when she was indicted, along with eight other accessories, on a felony charge of several petty thefts and larcenies on July 9, 1729. She was tried and convicted in the Hall of Justice of “Old Bailey”, located in the suburbs of London, on February 25, 1730 and placed in Newgate Prison, the only way out for her was to accept an offered pardon in exchange for “volunteering” to be transported to his Majesty’s Colonies and Plantations in America. For her sentence, she was given an edict by King George I, “His Majesty’s royal mercy on condition of transportation to some parts of America for a spare of fourteen years”. This edict stated that she would not be allowed to return to any part of Great Britain or Ireland for the term of her banishment. Her Transportation Bond was issued on March 9, 1730. Margaret became one of 106 prisoners whom Jonathan Forward contracted to transport aboard the “Patapscoe Merchant” from the Newgate Prison, City of London, County of Middlesex, England to Maryland on March 17, 1730. Such trips took between five to nine weeks to complete, depending on the weather and illnesses aboard ship, twelve people died on this particular voyage, which apparently was about typical. Capt. Darby Lux, the captain of the ship, was paid five pounds per head, even for prisoners who died en route, thus there was little incentive to see that they arrived safely. The convicts only received from one to five ounces of food per day and had to remain below decks in deplorable unsanitary conditions. Margaret amazingly survived the whole ordeal but one must wonder how much her health actually suffered. Upon arrival and in order to pay her passage, Margaret was cleaned up to be sold as a white slave on the auction blocks at Annapolis, Maryland. Tobias Phillips, a successful second generation tobacco planter from Old Rappahannock (now Richmond Co.) Co., Virginia, learned of the ship arriving in Baltimore, Maryland, and traveled 100 miles to meet Capt. Darby Lux and inspect the 94 surviving prisoners. Tobias Phillips purchased Margaret’s Bond which entitled him to fourteen years of service, and brought her back to his tobacco plantation in Virginia. While at the tobacco plantation, Margaret bore her slave master, TOBIAS PHILLIPS (1687-c1739)*, two illegitimate sons. Life on the plantation was hard on Margaret, as she did not live out her entire Bond of fourteen years, and she died there on the Richmond, Rappahannock Co., Virginia plantation before 1739. This is in evidence as there is no record that she ever received her “Freedom Dues” and she was also not mentioned in Tobias Phillips’ will dated on September 10, 1739. Margaret Laurence, Theft: Specified Place, about August of 1729 The Proceedings of the Old Bailey Ref: t17290827-32 ~ Original Text Margaret Laurence, of St. Andrew’s Holborn, was indicted for that she, together with Esther Morgan, not taken, did feloniously steal a Gold Watch, Chain, and Seals, value 24 1. a Gold Snuff-Box, value 18 1. a Diamond Ear-ring, one Velvet Gown and Petticoat, and other Suits of silk Cloaths, and divers other wearing Apparel, Silk and Linen, as Head-Dress, Ruffles, Laces, &c. to the sum of 10 1. and 40 Guineas, the Goods of Martha Thorold, in the Dwelling-House of the said Martha Thorold, the 9th of July last. Madam Thorold depos’d, That the Prisoner had been her Servant, but had been gone from her about a Fortnight; and that she went out to pay a Visit about half an Hour after Five a-Clock in the afternoon, the 9th of July last, and returning Home about a half an Hour after Eight, could not get any Entrance; whereupon her Footman went round about, and got in the Back-way, where he found the Doors backwards all open, and opening the fore-Door, let her in, saying, Madam you are robb’d; that she going into her Rooms, found her Cabinet broken open, and the Drawers, &c. all thrown about the Room, and the Goods and Money mention’d in the indictment, gone, and finding her Servants, and examining them; Betty Loyd pretended to have been found, and that the Robbery was committed by two Persons, who they did believe were Men in Women’s Cloths; and that the Servants did not own for a considerable time that they knew who the Persons were that had commited the Robbery. Elizabeth Loyd depos’d, That the Prisoner came about a Fortnight after she had left Madam Thorold’s Service, along with Hester Morgan, to their House; that they ask’d them to stay all Night, which they did, and all the next Day, ‘till her Mistress were gone out; after which, Margaret Laurence pull’d her into th Men’s Room, telling her, She had her Mistress and thrown her down on the Bed, took off her Garters, and tied her Hands, &c. with her Garters, and then went and rifled the House; that they were busy in doing it for about 3 quarters of an Hour, and afterwards she say the go out at the Back-Door, having each of them a large Bundle under their Riding-Hoods; but she could not tell what was in them. Lucy Hart depos’d, That She being busy in getting up Mrs. Thorold’s Head-cloaths, heard Betty Loyd shriek out, and presently the Prisoner and Hester Morgan came into the Room, and told her, They had a mind to rob Mrs. Thorold of her Money; that she desir’d them not to talk of any such thing; her Conscience would not let her consent to it; the the Prisoner replied, If Taylor and Weldon (two former Servants) had been there, they would have been glad of the Opportunity; that she not consenting, but crying out, Hester Morgan damn’d her, and threatened her, that if she made any Noise of Opposition, she would kill her; that they at first ty’d her, but afterwards let her loose again, and lock’d her up. Thomas Booth, the Constable, depos’d, That the Prisoner being apprehended, did at last own the Fact; that she had pawn’d a Pair of Stays a Gown and Petticoat of Mrs. Thorolds, and told them where Hester Morgan lodged, at one Forster’s, a Shoemaker in Tash-Street; that he went thither, and Hester Morgan being gone out, he demanded the Key; but that not being deliver’d, he search’d the Room, but not finding them; after menacing the People of the House, was told, that the Goods had been carried to a Trunkmaker’s in Holborn, which by Enquiry being found, they were inform’d that Morgan having bought a large Trunk the Things were put into it, and carried away by a Porter; the the Porter being found, he carried him to one Mr. Busby’s, where it was found; but Hester Morgan was not there, not had they yet had an Opportunity of apprehending her. Mr. Busby depos’d, That she had known Hester Morgan several Years, and took her for an honest Person; that meeting with her, she said she was coming out of Place, and desir’d her to recommend her to a Lodging in an honest House, whereupon she told her she might lodge with her, and the Trunk and a Bundle was brought in: The Constable added, That the Prisoner being ask’d the reason whe she had robb’d Madam Thorold? she replied, That she did it not for Want, but for Spite, she having us’d her ill. Mr. Chambers, the Pawn-broker, depos’d, That having heard of Madam Thorold’s being robb’d, and suspecting that the Stays, Gowns, &c. which the Prisoner had pawn’d to him, were Madam Thorold’s, he went and acquainted her he had such Things, which she having own’d, they were produced in Court, own’d by the Prosecutor, and sworn to be pawn’d by the Prisoner. The Prisoner in her Defence pleaded, that she receiv’d those Cloaths from Hester Morgan, to pawn for her, who pretended that Madam Thorold had given them to her. She pleaded likewise, that Elizabeth Loyd desir’d her to take off her Garters, and bind her with them and likewise to Gag her, that her Mistress might have no Suspicion of her; that the Evidences, Loyd, Hart, and Morgan, had contriv’d the Robbery, and she had been sent to for Several times to commit it, and that they were all four to have gone down into Wales; and that she had note of the Things but the Gown, Petticoat and Stays before-mention’d, and knew but of 12 Guineas to have been taken by Morgan. The Fact being plainly prov’d, the Jury found her guilty of the Indictment. Death. At receiving Sentence, the Prisoner did not, as usual, plead her Belly, but begg’d of the Court to consider that she was a young Person, and threw herself upon the Mercy of the Court.

Stephen Hopkins, from Jamestown to Plymouth.

The shipwreck survivors have finally made it to Jamestown. Their journey was mind-blowing but their troubles are not complete. The ships in the Chesapeake Bay were finally recognized as English so they were not killed by cannon fire. The Patience and Deliverance expected a thriving colony but they were greeted with a truly horrific sight. This time in Jamestown was called the “starving time”. Out of 500 original colonists only about 100 survived. The fort was in ruins, the natives were hostile, there was no food and the survivors of the starving time were thin and weak. The bay had been nearly fished out and their nets had been left to rot. The new arrivals expected provisions and thus had not brought anything with them from Bermuda. This was a very bad situation. They didn’t have enough food for the 100 already there but now had an additional 40 mouths to feed.

Governor Gates made a speech announcing that if they could not find food soon that he would make room on the boats and take all the people out of Jamestown to Newfoundland where they could then get passage back to England from fishermen and trading ship. A week passed and things were not looking up. Fishing expeditions returned with little or no fish. Gates made the decision that it was now time to abandon the colony. The group had sailed as far as anchoring on Mulberry Island to await the tide when suddenly appeared three boats in the distance with a longboat heading their way. Thomas West (Lord De La Warr) was there to greet them. He had brought with him 150 new and healthy colonist and enough food and provisions to last a year. They went back to Jamestown where Stephen would remain for the next 5 to 7 years. De La Warr remained governor for 10 months and was then replaced by Sir Thomas Dale. He was severe in his punishments. Stealing even as little as a grain of corn was punishable by death. Not all punishments were mere hangings though, many were actually burned at the stake. The punishment for being tardy to work was a public whipping. The company actually started to prosper.During Sir Thomas Dale’s first year as Jamestown’s governor, William Strachey’s account of the wreck of the Sea Venture reached the hands of William Shakespeare. His play “The Tempest” is based upon Strachey’s work. The character of Stefano is based on Stephen Hopkins.

Stephens’s wife Mary died while he was serving his tenure in Jamestown. She was buried in Hursley Parish on 10 May 1613. Her estate records refer to her as a widow but her burial records refer to her as wife of Stephen Hopkins.

In April of 1616 the marriage of John Rolfe to Pocahontas was performed by Reverend Richard Buck. Being the psalter for Reverend Buck, it would seem that Stephen was also in attendance for this ceremony. It is known that Stephen was called back to England and released by Governor Gates in 1616 because of the death of his wife Mary. He sailed back to England on the same boat as his fellow Sea Venture castaway John Rolfe and Rolfe’s new wife Pocahontas.

Stephen lived in the south part of London after his time in Jamestown. The first record of him back in England is his marriage to Elizabeth Fisher at St. Mary’s White-chapel on 19 February, 1618. Their first daughter Damaris was baptized at St. Mary’s 3 March, 1618.

The Brownist-Separatist was an offshoot of the Anglican Church. They felt that the Anglican’s were too much like the Catholics though. They felt that the church needed to be purified of all Catholic influence, thus the moniker “Puritan”. The Separatist were often punished and jailed for their non-conformity to the Church of England. A group of Separatist from Leiden congregation left England for Holland to avoid prosecution. This group included William Bradford. The Separatist in Holland joined with a group in London to immigrate to Northern Virginia under the auspices of the Virginia Company of London. All paperwork was completed in early July, 1620. The Mayflower was hired and the Hopkins family moved on board by mid-July. The Leiden congregation arrived to South Hampton on July 22nd from Holland. After much infighting, the Mayflower and Speedwell departed South Hampton on August 5th. They did not get very far and had to pull into Dartmouth to repair the Speedwell. She was leaking and in need of repair. After 2 weeks in Dartmouth the Speedwell was ready to sail. This time the ships made it 300 miles out to sea before the Speedwell starting leaking again, this time at an alarming rate. They returned this time to Plymouth where a decision was made to abandon the Speedwell. Some of the Speedwell passengers disembarked at this point and others joined the passengers on the Mayflower, bringing the Mayflower to a count of 102 passengers. Finally on September 6 the Mayflower left England.

When the Mayflower was set to sail back in July Elizabeth Hopkins was 6 months pregnant but with the numerous delays by the time they set sail Elizabeth was 8 months pregnant. Sharing a 50 x 25 foot space with 101 other passengers must have been grueling for Elizabeth. She gave birth to her young son mid-voyage. Stephen and Elizabeth named their young son Oceanus because he was born in the middle of the ocean. There was one other child on the Mayflower; Peregrine White was born on the Mayflower after it landed in Cape Cod Harbor. The voyage must have been arduous for these women.

On November 9, 1620 the ship finally arrived in America at Cape Cod, far north of where they had patents in Virginia. They discussed whether or not to remain in this area or risk passing through the treacherous Pollocks Rip a second time. The voted to stay and that left a void in leadership since the current governor held no authority other than in Virginia Colony. Stephen must have been extremely worried at this point. This is the same scenario he faced in Bermuda where he was accused of mutiny and barely escaped his sentence of death. To resolve this problem the Pilgrims wrote up a legal document establishing a government for their new colony prior to settling on shore. Stephen Hopkins was the 13th signer of this document, better known as the Mayflower Compact on November 11, 1620. After researching the land and sea they decided that the land on Clarks’s Island was good for farming and the natural harbor good for shipping. The started building their settlement at that site on December 18. They called there new settlement the Plymouth Plantation after the last place the saw of their home country.

The first winter in the Plymouth Plantation was harsh and the settlers had no food. They arrived too late to plant and soon ran out of food. Cold, hunger and illness took their toll on the settlers. By spring 45 of the original Mayflowers passengers had died.

That spring the Pilgrims met the Indians. There first encounter was with a man named Samoset who just walked up and said “Welcome Englishmen”. Samoset had learned a few words from traders who passed by the coast. Samoset later brought another Indian whose name was Tisquantum, better known as Squanto. Squanto learned to speak English after being kidnapped and then being rescued by local friars in Malaga Spain. He made his way aboard a ship to the Newfoundland Company and then back to his home of Patuxet (now Plymouth Plantation). Now the trading and friendship between Pilgrims and Indians could commence. Samoset and Squanto always stayed at the Hopkins home whenever they came. The Indians introduced the settlers to corn and taught them how to grow it. The seeds they brought from England on the Mayflower produced very little crops but the corn harvest was tremendous. They were able to grow enough food to see then through the next year and further.

Fall arrived and the colony was going to be well fed and well housed that winter. They decided to celebrate their good fortune with a great feast. The feast lasted several days. Not only did they eat well on corn, fish and fowl many of the local natives showed up as well bearing venison. There was dancing, shooting contest, and games. Looks like a good time all around. This was the first Thanksgiving in America.

Stephen Hopkins owned a tavern and was active in politics and community affairs until he was charges with and found guilty of overcharging for ale and cider. He was also charges with allowing drunkenness in his tavern and serving on ale on Sunday.

Stephen died between June 6, 1644 when he wrote his will and July 17, 1644 when his will was proved.

Stephen Hopkins, 1581 -1644 The adventurer

We all have fascinating ancestors. It takes time and effort to find them. Well, Stephen Hopkins story is doozy. Stephen was baptized 30 April 1581 in Upper Clatford, Hampshire, England. Baptismal records show his parents as John and Elizabeth Hopkins. The next time I can find Stephen on any records is 13 March, 1605 for the baptism of his daughter Elizabeth Hursley, Hampshire, England. This record shows his wife as Mary. Some think she was Mary Machell. His daughter Constance (Mayflower passenger) was baptized on 11 May, 1606 and then son Giles on 30 January, 1608. (Was Giles named for Mary’s father? Records show the will of Robert Machell of Hursley mentioning Giles Machell who was of age to be Mary’s father. Later in 1608 Stephen signed on as the psalter for Reverend Richard Buck. (The psalter he was reading from was written by Thomas Sternhold and co-authored by Oxford minister John Hopkins. Was this John Hopkins his father?)

On 2 June, 1609, Stephen left his family behind and boarded the Sea Venture heading to Virginia to resupply the new Jamestown Colony. The Sea Venture was the flagship of a fleet of 7 carrying Jamestown’s next governor, Sir Thomas Gates, Admiral Sir George Somers, Captain Christopher Newport, the colony’s new minister Reverend Richard Buck and his psalter Stephen Hopkins. The fleet took a northerly route to the Jamestown Colony to avoid the Spanish Armada who was active at this time robbing English ships. The fleet enjoyed smooth sailing until Monday, July 24th. They were struck by a hurricane. The ship sprung a leak and began to “spew her oakum”. Now she had many leaks. By the 2nd day of the storm the flooding of the ship destroyed the food supply and drinking water. They lost 10,000 pounds of hardtack alone. The storm continued to rage and battle the boat. Just about everyone had given up hope of survival. They were exhausted from continual bailing, and had no potable water or food.

On Friday afternoon, 4 days after the onset of the storm, it started to abate. Then someone yelled “Land!” Uh oh, another problem, the Sea Venture was sinking and could not be anchored for the crew and passengers to take a longboat ashore. The decision was made to go full speed ahead in an attempt to beach the boat. The ship wedged between two large rocks and they crew and passengers were able then to take a longboat ashore. Miracle of miracles, everyone survived. Word soon spread amongst the survivors that they had landed on the Isle of Devils. This island was said to be haunted by ghosts and spirits and to be enchanted. This island is now called Bermuda. It is in the Bermuda Triangle. I wonder if anyone slept that first night, trees still swaying whistling from the storm, lightning flashes still from the storm. The native cahow bird had an unusual cackling.

The search for food and shelter on the island proved to be fortuitous. Palm leaves made excellent roofs. Wild berries were plentiful as well as the bounty of the sea. They ate a lot of fish and turtles. There were wild hogs on the island as well. Even though the castaways were well fed and well housed they still needed to get to Jamestown. They gathered what tools they could from the Sea Venture and set about building 2 new boats.

As time passed discontent began to arise among the survivors. Stephen Hopkins was one of the rebels. William Strachey said Hopkins “more subtly began to shake the foundation of our quiet safety”. Stephen was questioning the authority of the leaders of their group and expressing dissatisfaction with their authority since they were neither in the Virginia Colony nor on sea. Unfortunately denying the authority of the governor was considered mutiny which was punishable by death. Stephen was tried and found guilty. He was scheduled to be hanged. Secretary Strachey states: “But so penitent he was, and made so much moan, alleging the ruin of his wife and children in this his trespass, as it wrought in the hearts of all the better sort of the company, who therefore with humble entreaties and earnest supplication went to our governor, whom they besought (as likewise did Captain Newport and myself) and never left him until we had got his pardon”. Not much more is heard about Stephen on the island of Bermuda after this. He kept to himself and stayed behind the scenes.

Towards the end of April both boats were ready to be launched. They were named the Deliverance and Patience. On 10 March, 1610 the group finally set sail for Jamestown. Seven days later as they were pulling into the Chesapeake Bay, James Davies set off a warning shot from a cannon at Fort Comfort. At long last, Jamestown.

To be continued

Nicholas Gibbs, 1733 – 1817 My 4th Great Grandfather

Nicholas Gibbs was born September 29, 1733 in Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany. I’ve also seen references showing him born in Village of Wallruth, Krumbach, Baden, Germany. In the family there were three brothers Peter, Abraham, and Nicholas, and two sisters, Mary and Catherine.

Abraham was the first to arrive in America, sometime prior to 1747. He probably came in through Philadelphia or Baltimore. His residence was in Fredericktown, Maryland in 1846. Nicholas arrived in 1747 at age 14. According to Rootweb, he left home after an argument with his father carrying 30 guineas. Thirty guineas were only enough for half the passage to America so he worked on board ship for the other half of the passage.

After his arrival he served five years in the English army during the French and Indian War. During this time his brother Abraham heard he was serving in the military and sought him out. He lived with his brother for a short time prior to moving to Orange County, North Carolina where he married Mary Ephland in 1764. He sold his property in Orange County and moved to property along Beaver Creek in Hawkins County, Tennessee in 1791. This area became part of Knox County in 1792. The Gibbs farm is now an historical site.

Nicholas Gibbs was given a grant of 100 acres on Beaver Dam Creek (Knox County) for “services in the Continental Line” (Land Grant Records, Raleigh, North Carolina, Book 88, Page 193, Grant 257, dated March 7, 1796). This grant is also recorded in Knox County, Tennessee, Book B, No. 2, Registrar’s Office, and his name appears on the Knox County roll of Revolutionary War soldiers as having participated in the Battle of King’s Mountain. He served with John Sevier in the militia as part of the Overmountain Men.

I copied the following from the tngenweb site.

The Battle of King’s Mountain by C. Hammett, Coordinator Tennesseans in the Revolutionary War

King’s Mountain is unique in America’s history: This battle—fought by 1,000 plus militiamen—without orders, formal military training, uniforms or provisions, and with no promise of pay—against the supposedly “superior forces” (1) of noted English Col. Patrick Ferguson—is credited by most early historians with having changed the course of the Revolution in the South, and may have even insured that the original number of colonies in these United States of America would be thirteen, not ten. (2)

In only one hour and five minutes, the American Whigs (Patriots, Rebels) totally decimated Ferguson’s American Tories (Loyalists, Royalists), with every last man of them either dead or taken prisoner, and the Colonel himself left dead on the battlefield—having signed his own death warrant less than a month earlier when he sent a message from his camp in Gilbert Town, Rutherford County, North Carolina, to the “officers on the Western waters” (west of the Blue Ridge) that if they did not “desist from their opposition to the British army, and take protection under his standard, he would march his army over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay their country waste with fire and sword.” (3)

Col. Ferguson’s warning was the result of his frustration over the refusal of most of the Overmountain men (east Tennessean and southwestern Virginians) to take the loyalty oath and to cease providing safe harbours for militiamen from the Carolinas and Georgia (who had eluded him after the August 16th defeat of American General Gates and the American army at the battle of Camden by retreating ”overmountain” to the “western waters”).

It did not have the expected results: The message was delivered to Sullivan County, North Carolina (now Tennessee) Militia Colonel Isaac Shelby of Sapling Grove (present-day Bristol, Sullivan County, Tennessee), who immediately rode out to confer with neighboring Washington County, North Carolina (now Tennessee) Militia Colonel John Sevier. The two men agreed that the best solution was to “march with all the men we could raise, and attempt to surprise Ferguson, by attacking him in his camp, or at any rate before he was prepared…” (4)

Col. Shelby also convinced Col. William Campbell, commander of the county militia in neighboring Washington County, Virginia, to join him and Sevier on 25 Sep 1780 at Watauga, the time and place they had appointed for their rendevous. Also “overmountain” at the time were Cols. Charles McDowell and Andrew Hampton and their militiamen (from Burke and Rutherford Counties, North Carolina, respectively), and when the five county militias assembled on the 25th, they were over 1,000 strong. The following day they began their march across the mountains, and on September 30th met up with Cols. Benjamin Cleveland and Joseph Winston and their 350 militiamen from Wilkes and Surry Counties, North Carolina (respectively), bringing their total to almost 1,400. (5)

The seven officers were well aware that they and their men were “amateurs” on a regular field of battle (although the Overmountain men were well-experienced in Indian-fighting), and also that they did not have the proper authority to take the action they contemplated. On October 4th, they dispatched by Col. McDowell (who left his brother, Joseph, in charge of his troops) a Request to General Gates for a general officer to command them, but in the meantime elected Col. Campbell temporary commander, and continued to march toward Gilbert Town. (ibid.)

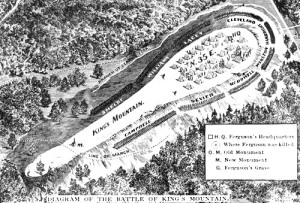

Diagram of the Battle of King’s Mountain

Created from Goldbug’s AniMap

The next day they learned that Ferguson had been apprised of their approach, and had left Gilbert Town. The council of officers met that night and determined to pursue him no matter to what ends. Leaving behind their footsoldiers and weaker horses to catch up when they could, the men continued forward, and on the 6th of September, at Cowpens, South Carolina, were joined by Col. James Williams of Granville County, North Carolina, who was accompanied by about 400 men (largely from Sumter’s South Carolina troops under Colonels Hill, Lacey and Graham), but also including 60 militiamen from Lincoln County, North Carolina under Col. Andrew Hambright, and another 60 South Carolina militiamen under Major William Chronicle. Colonel Williams, also in pursuit of Ferguson, was able to advise them of Ferguson’s location: He was atop King’s Mountain. (ibid.)

After an all-night forced march in pouring rains, at three o’clock the afternoon of the following day, on the 7th of October, the men circled the mountain and charged.

Only one hour later, Ferguson and scores of his troops were dead, and the remainder, many wounded, taken prisoner. The rest is history… Or is it?

Nicholas died in 1817 in Knox County, Tennessee. He is buried in the Gibbs family cemetery in Coryton, Tennessee.

Daniel Doane, 1666 – 1743 Astrologer and Rebel

Daniel was born in 1666, in Barnstable, Massachusetts. He was the second son of Deacon Daniel Doane and Constance Snow. He died in Newtown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania on November 1, 1743. He is the Grandson of John Doane, (1st Assistant Governor of Massachusetts and Great Grandson of Steven Hopkins of the Mayflower.

He appears to be the rebel in the family. He was the first of our ancestors to leave the Puritan religion. He joined the Quakers. The Puritans did not approve of Quakers. They believed all religions with the exception of the Purified Anglican Church were heretical. This places Daniel in the category of an heretic. I get the feeling his may have disowned him because of this. In his father’s will all his brothers and sisters received land and other good stuff, Danial only received one pound. This fact does not prove he was disowned. He may have collected his share prior to moving to Pennsylvania as well.

According to “Yates Publishing U.S. and International Marriage Records, 1560-1900” Daniel married Mehetable Twining in 1686. He and his wife Mehetable joined the Friends Congregation of Sandwich, in Massachusetts in 1696. Thereafter Daniel and Mehetable move to Newtown, Pennsylvania. He died there on August 8, 1743.

We know that Daniel was literate because somewhere along the line he started reading about and practicing astrology. He liked to predict the future using the stars. This caused a lot of problems with the Society of Friends. He was reprimanded several times and finally he was disowned by the church. I cannot find a record of him being welcome back into the Society but he was buried in Middletown Friends Cemetery, located in Langhorne, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, USA.

Below is a copy of his apology to the church regarding his astrology habits. Does this apology prove his rebel status?

Daniel’s “Apology”

“Although Daniel began well in Bucks Co. and was at first, it is thought,

a religious teacher among Friends, only a few years after his arrival in

Pennsylvania his investigating spirit led him to study the stars and the

influence of the planets upon one another. But reports ‘that Daniel Doane

should meddle in predicting astrologie’ brought him into conflict with his

Meeting, which lasted almost continually until he was disowned in 1711. He

had a way of assuming the defensive which involved the frequent sending of

committees to parley with him; but Daniel, strong in his sense of the

right of private judgment and of free toleration as to opinions, treated all

charges and committees with ‘unseemly expressions’ and ‘contemptuous

flounts.’ From time to time, however, he would send in written apologies

and other papers, one of which was as follows:

“‘In as much as many by their consulting the figures of conceptions, and

with revolutions and perfections, presume to tell what is contingent to bear

upon earth, either weal or woe, while they themselves are ye bitter source, and are shut up, under ye oxit of ye animated spirit and become fools to ye

wisdom of Egypt; and inasmuch as it has much amused the minds of many

concerning me because I have done some things of that nature as to prediction, and some have been inquisitus to see ye aphorisms and schemes

by which I did work them and though I did never show it unto any, yet I do

say ingeniously and without mental reservation, that I never was inclined,

much

less to study, any magick art or southing divination or negromantic

trick.’

“At length tired of Daniel and his doings, the Middletown Meeting, after

many expressions of sorrow ‘that he is so wayward’ and prayers ‘that he may be brought back to ye truth’ disowns ‘the said Daniel Doane to be one of us,’

and ‘we being clear of him, his wickedness lies upon his own head.’

William Owens, 1820 – 1901

William Owens was born on October 5, 1820. He was the oldest son of John and Sarah Gibbs Owens. On January 25, 1844 at age 22 he married Sarah Lee Howell. She was only 12 at the time. William and Sarah raised their 15 children on a farm in Vestal area of South Knoxville, Tennessee. William died on April 11, 1901. My cousin Amy told me that he died of smallpox and had to live in the smokehouse to prevent the spread of the disease to his family. I cannot find a death certificate or a history of smallpox in Knox County in 1901.

John Owens, Williams’ father committed suicide by hanging himself in the barn in 1860. This was a short time after beating William with his cane. William had the burden of being the person who cut his father down from the rafters.

William was in his early 40’s during the Civil War. He did not fight on either side of the conflict. He was considered a “mossback”. Mossbacks were southerners who hid in caves to avoid conscription into the Confederate army. The womenfolk took different routes to the cave to deliver food and supplies daily so that there was no trail leading to the cave for the army to find. Here is a map of the cave he lived in.

Here is a quote from Oliver Templeton Perry’s book “East Tennessee and the Civil War” published in 1899 by the Robert Clark Co. Publishers, Cincinnati, Ohio, describing the Owens home:

Here is a quote from Oliver Templeton Perry’s book “East Tennessee and the Civil War” published in 1899 by the Robert Clark Co. Publishers, Cincinnati, Ohio, describing the Owens home:

“It is not generally known in Knoxville that Governor Sevier one built and lived in a house one mile south side of the river, opposite the city on the left side of Maryville Road. The house was built of hewn logs with a foundation of marble. Now it is weather boarded on the outside and ceiled on the inside. It once belonged to Mr. John Wrinkle and now to Mr. William Owens. The fact that Mr. John Sevier once lived in it, is well established by tradition and the testimony of old people, as any fact can be”.

Myrtle May Hinton Berry, 1900 – 1979

Myrtle was the youngest child of David and Lula Rhodes Hinton. She married Ann Drury Berry on September 20, 1922. They are in the census in Knox County Tennessee in 1930. They show up in Albuquerque, New Mexico in 1932 and back in the Knoxville city directory in 1833. Drury had tuberculosis so I am making the assumption that they moved to New Mexico because of that. The dust bowl was happening at that time so I can only guess that they felt it was healthier in Tennessee, or maybe they just missed their home. Drury lived until 1947 and his death certificate states he died of tuberculosis. Myrtle never remarried.

When I was a child we visited yearly. I remember her as being kind and always felt she loved all she met. She was still pretty into her 60’s. I always had the feeling that she missed her husband. I like to think that they may have had the big romance in the family. I can’t think of her without thinking romance. (Reasons in story below)

Myrtle was the very definition of the eccentric cat lady. She fed feral cats and they would follow her around. Her closets were full of toilet paper and Lifebouy soap. Every year when we were leaving from our family visit to Tennessee we would stop by to say our good byes. Her sister and brother-in-law (Walter and Maud Hinton Cupp) lived next door. Walter and Maud always gave us girls a silver dollar but Myrtle always gave us toilet paper. Toilet paper was probably very practical, since public restrooms were notoriously dirty and lacking in supplies back in the 1960’s.

So here’s the good story. It was the summer of 1973. I have a new baby (born the previous November), just turned 20 and called my father for a rescue from an unsafe situation. He and my mother just happened to be in Knoxville at that time and I was in Clarksville, Tennessee. Mom and dad showed up within 8 hours and took me back to Knoxville. When we arrived in Knoxville, my dad’s mother’s home was full and there was not enough room for all of us. Myrtle volunteered to take me in along with the baby. When we arrive at Myrtles we help her clean out a room for us. Myrtle says “Nobody’s slept in this room since Drury died”! We started stripping the bed and dust was flying everywhere. On the wall was their marriage certificate in a beautiful frame. The dresser still held his collars. (It was like the Drury Shrine.) We finally got the room set and now it’s bedtime. Myrtle advised me that she had birds nesting in her chimney and lit candles in the hearth every night to keep them from entering the house. So here I am, 20 years old with a baby sleeping in the Drury Shrine where nobody has slept since he died and the lights from the candles flicker on the walls and birds singing and fluttering in the chimney. I actually fell asleep until about 2:30 in the morning. That’s when it happened. Myrtle suffered from nightmares and sleepwalking. She started shrieking and walking around the house. When she walked in front of the fireplace she left ghostly shadows on the wall. I did not fall back to sleep. I held my baby and sat and trembled on the edge of the bed unable to move. I did not spend another night there. We were going back to Florida the next morning anyway. So not only was Myrtle my beloved great-aunt she also provided my experience into the 1950’s B-movies.

Mapping your ancestors with Google Maps

For a long time I’ve wanted to map the locations of my ancestors on Google Maps. I’ve wanted to do this in part to get a visual image of where my ancestors come (as they say a picture paints a thousand words) but also to help my distant DNA cousins figure out how we might be related.

Today I got around to try this, and the good news is that it’s incredibly easy. Below is a walk-through of the process.

View original post 1,410 more words

Elizabeth LIndsey, My 3rd Great grandmother. 1790 – 1860

This story is found in the book: Our East Tennessee Kinsmen, by Aurelia Cate Dawson: 1962

Relayed by James G. Cate of Kodak, TN b. 1862, d. 1937 (grandson of James T. and Elizabeth Lindsey Cate) as told by John Enyard Cate

“Betsy went to the spring for some water and some Indians stole her when she was 14 years of age. (1804). The Indians kept her about 6 months. She was to be married to an Indian Chief the next day. An Indian woman told her that she would fix it so she could get away when the men went out to catch game for the wedding. While they were away the Indian woman put her in a hollow log and told her if a little dog came in the log for her to kill it, for if she did not kill the dog the Indian men would find her by the dog. The dog came in the log and Betsy had to smother the dog to death.

The Indians returned and sat on the log where Betsy was hiding. She could hear them calling the dog and whooping the War Cry. After the Indians went away she came out of the huge log and crawled on her hands and feet. She lost her bonnet and tore her clothes off on her crawling through the brush. She traveled only at night for she was afraid to travel in the day for fear that the Indians might see her. She traveled a week before she came to a house. The first was a storehouse. She told the man her trouble and that she was hiding from the Indians. For her torn clothes the storekeeper gave her a suit of men’s clothing and a man’s haircut. The man told her to travel the road and not after night. She came to another house and stayed there for a few days. The man of the house took her home as he had been through that part of the country and her people were proud that he had brought her home. The flax wheel of Betsy Lindsey Cate came over on the same ship as Nancy Hank’s, according to Sallie Koontz, a great granddaughter.Eli